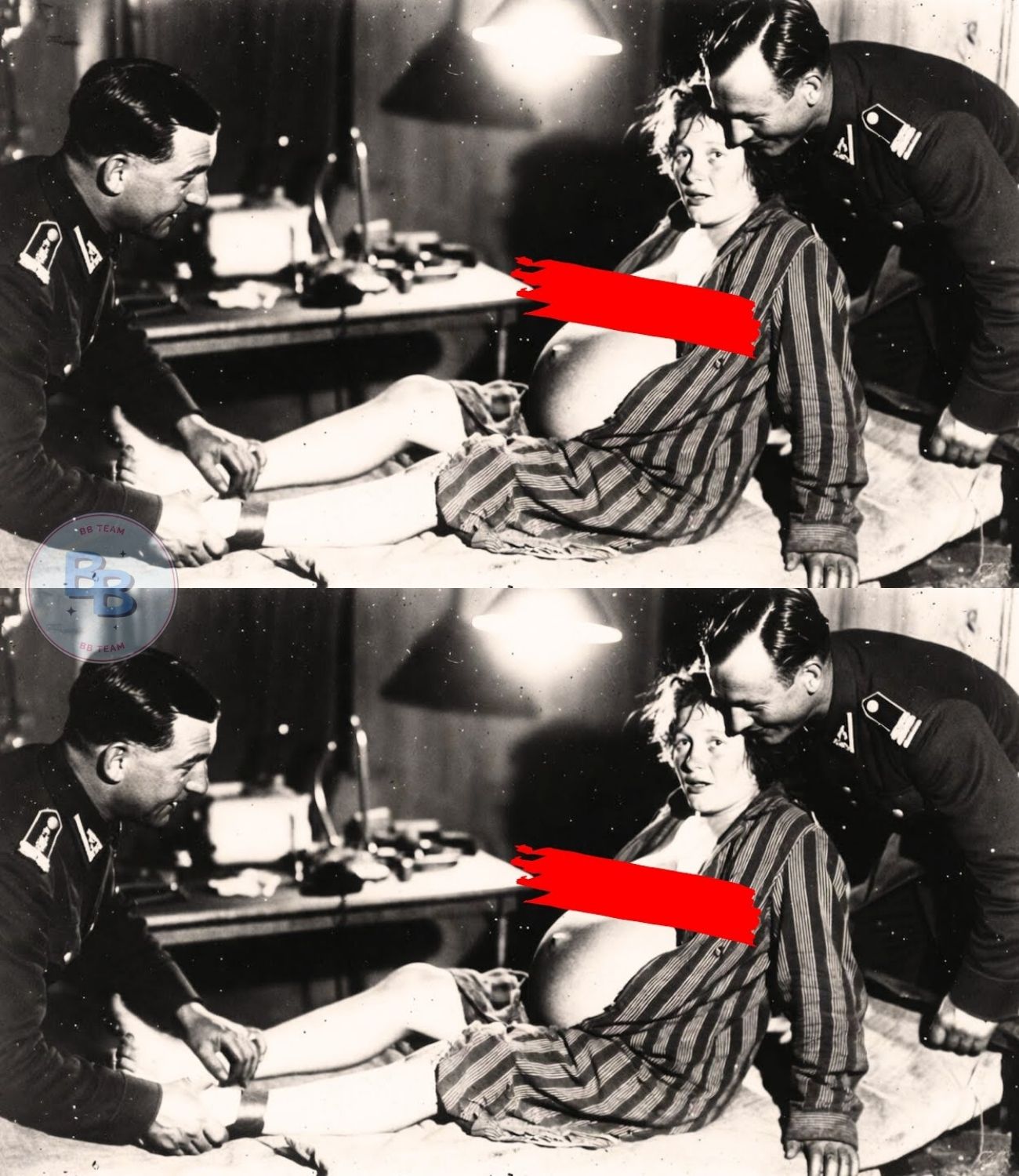

She was eight months pregnant” — What German soldiers did to her before she gave birth

There are things we don’t forget even when we try. The noise of boots pounding the wooden floor your house at three in the morning. The smell gun oil mixed with sweat masculine. The feeling of a hand rough squeezing your arm for that another pushes your belly h month as if he were an obstacle on the path.

My name is Victoire de la Cross. I am years old and for sixty of them, I kept a secret that must now be revealed, not because that I want it, but because dead people can’t speak and someone must testify to what they has arrived. When the German soldiers took me snatched from my home that night in March4, I was 33 weeks pregnant. My son was moving so much that I could barely sleep.

He gave blows feet in my ribs as if he wanted already come out, as if he knew that something terrible was going to happen produce. I didn’t know it yet, but he was right. What they got me done before childbirth has no name in no language that I know and what they did next was worse. They didn’t take me alone. We were ten women that night, all young, all beautiful enough to attract attention.

Five were pregnant like me. The others were virgins, engaged, young mother. We have been choose as one chooses fruit a market. They entered the house through house with lists, lists containing our names. This means that someone from our own village had delivered. Someone we acquaintances, someone who took the coffee in our kitchen.

I lived in Tul, a working-class town in the center of France, known for its arms factories. My father worked in the factory of weapons. My mother sewed uniforms for the German army under occupation forced. We had learned to lower the eyes when soldiers passed by, not to not answer when they spoke to us, pretend not to exist.

But That night, pretending didn’t work enough. Henry, my fiancé, tried to protect. He threw himself in front of the soldier who pulled me towards the door. I have heard the sound of the rifle butt, hitting his head before seeing the blood. Then silence. My mother screamed. My father remained motionless, his hands up, trembling.

I looked in back one last time before being pushed into the truck. I saw my house. I saw my bedroom window where the baby’s trousseau was folded on the chest of drawers. I have seen all my life disappear while the engine truck swallowed up any chance of return. Inside the truck we There were 17 bodies packed together.

Some were crying, others were in a state of shock. A 16 year old girl vomited on my feet. I held my stomach with my two hands and I prayed that my son is not born there in the darkness among terrified strangers. We don’t didn’t know where we were going. We don’t didn’t know why. We knew only when the Germans take women to the middle of the night, they generally do not return not in the same way.

The journey took hours. When the truck finally stopped, I heard voices in German outside, brief, dry orders. The tarpaulin was pulled and the light of lanterns blinded us. We have been forced to descend. Some have stumbled. I almost fell. But one hand held me by the elbow. It wasn’t kindness, it was efficiency.

They needed us to arrive intact. We were in a camp work near Tules. I knew this place. Before the war, it was a farm. Now, barbed wire fences, towers of guai, rotten wooden huts, smell of sewage and burnt flesh. There had other women there. French, Polish, Russian, very young, very this empty look that I will only understand later.

The look of those who don’t wait for anything anymore. If you listen to me Now you might be thinking that it’s just another story of war, another sad story that will unfold end with a heartwarming lesson. This will not be the case because what happened in the following weeks has no possible comfort. And if you think you’ve already heard Worst stories, I guarantee you you haven’t heard yet mine.

We were separated first night. Pregnant women have were taken to a barracks different. They said we would receive special care. A relief passed through my chest for a second, only one second because when the door of this barracks closed behind us, I realized there was no bed, no cover. There was only a German officer, tall, with eyes clear, smoking a cigarette, we observing as one evaluates cattle.

Hespoke French fluently, without accent. It was worse by a certain way. This meant that he understood every word we said, every plea, every cry and which he chose to ignore. He walked slowly between the five of us, stopping in front of each belly, touching the tip fingers as if he were testing the maturity of a fruit. When he arrived in front of me he stopped.

He is stood there, motionless, staring at me. I didn’t look away. I don’t don’t know why. Maybe from the pride, maybe challenge, maybe just frozen fear. He smiled. This wasn’t a nice smile. It was the smile of someone who had just win something. He pointed to me and said a word in German to the soldier at next to him.

The soldier pulled me by the arm and took me outside. The four others stayed behind. I have heard their cry begin even before leave the barracks. Again today, I don’t know what’s wrong with them happened that night. I don’t know whether they had a worse or better fate than mine. I was taken to another building, smaller, cleaner. There was a bed, there were toilets, there was a window with a curtain.

For a stupid moment I thought maybe, just maybe, I was going to to be spared, that he had chosen me for protect me, that my big belly, my baby living inside me, would a sufficient shield. I was young, naive. I still believed that the monsters respected limits. He entered the room two o’clock later.

He locked the door behind him. He took off his jacket slowly, carefully folding it over the chair. He lit another cigarette. He looked at me. I was sitting on the bed, hands on my belly, trying to make me more small. He came closer. He got sitting next to me. He placed his hand on my face. His palm was warm. His fingers smelled of tobacco and metal.

“You are beautiful,” he said Perfect French. “Your baby is going to be born here under my care. You will thank me for that.” I didn’t thank him. not that night, nor during the 27 nights which followed. If you listen to this story now, wherever you are in the world, know that every word that I say is real, every detail, every horror.

And if something in you ask to stop listening, I understand, but I couldn’t stop to live. So please don’t stop listening. Leave your mark here in the comments. Tell me where you are from so that I know that I am no longer alone. so that those who do not have survived know that someone testifies again. The first nights he only observed me.

He sat on a chair in the corner of the room, smoking, asking questions. My name, my age, how long pregnant, if it was a boy or a girl? I I replied in a low voice, fearing that any bad word costs me life. He seemed satisfied. He said I was polite, that I understood how things worked here. The fifth night, he touched my stomach slowly, like if he had the right.

He felt my son kicked and laughed, a short, almost childish laugh. “Strong”, he said, “It will be a fighter. I have bit my lip until it bled so as not to shout, so as not to push this hand away, because I knew that if I resisted, he wouldn’t hurt me. He would do harm to the baby. Last night he raped me for the first time carefully, slowly, as if he were giving me a favor, as if my huge belly was only a technical obstacle to bypass. He turned me on my side.

He held me by the hips and that he was doing it, he whispered to my ear that I should not be afraid, that he wasn’t going to hurt the baby, that he liked me. Afterwards he slept in my bed. I stayed awake, Staring at the ceiling, feeling my son moving, wondering if he could feel what was happening, if he knew that his mother was destroyed while he was growing up. The days blended together.

I no longer counted. I measured the time differently. How many times he came at night? How many times my son was kicking after, how many times I thought of Henry and me asked if he was still alive, if he was looking for me, if he knew that I was carrying our child in a hell that he couldn’t imagine.

The commander was called Stormban Furer Klaus Richter. I learned his name because he repeated. He wanted me to say it. He wanted me to pronounce it correctly, with respect, as if we were lovers and not lovers and prisoner. He was 38 years old. He was married, he had three children in Bavaria. He me showed their photos, two boys and a girl, blond, smiling, dressed intraditional costume.

He said he loved them, that he missed him. Then he turned to me and did what he was doing. He wasn’t the only one. Other officers sometimes did not come in my room. Richter did not allow not that. I was his exclusive property. But I heard them in the others barracks. The screams, the supplications, the sudden silences that were worse than the screaming.

One night, I heard a woman screaming Polish for hours. In the morning, she no longer screamed. We never have it reviewed. There was a nurse French in the camp. Her name was Margaot, perhaps fifty years old, skinny, gray hair. She had been forced to work there because her husband had joined the resistance. She checked on me once a week, took notice, listened to the heart of baby with an old stethoscope.

She almost never spoke. But one times, as she placed her hand on my stomach, she whispered. Don’t fight not. Survival first, justice later. I didn’t understand at the time. I thought that surviving and fighting was better. She had seen other women pregnant before me. She knew what happened to the one who resisted.

She disappeared. Or worse, they gave birth and their baby disappeared. Margot was trying to save me from the one way she knew in me advising me to keep quiet, to lower my voice head. to let my body be used so that my child can live. But how do we do that? How does a mother can she allow herself to be destroyed while protecting what is growing inside her? Every night I split myself in two.

He there was victory which suffered, which closed her eyes and imagined that she was elsewhere. And there was the victory that kept one hand on its belly, which mentally sang lullabies, who promised his son that everything would be fine, that mom was strong. that mom was going to protect him. The weeks passed, my stomach was getting bigger, the baby was going down.

Margaot told me that it was for soon, a week, maybe two. I was afraid, afraid of giving birth in this place, afraid of what would happen after. Richter spoke to me more and more more of the baby. He said he would watch that they receive good care, that he would be well fed, that he would have a chance.

But he never said your baby, he said baby. As if the child no longer belonged to me. A evening, he came in with a bottle of French wine, good wine stolen from a cellar somewhere. He completed two glasses and expected one. I refused. About the baby, I said, he laughed. You are virtuous even now. This is what I like you, Victoire.

You are not not yet broken. I didn’t know how to tell him that I I was broken the first night, that this that he saw were only the pieces who still held together habit. He drank both glasses, then he sat next to me and talked, really spoken. He told me about his life, his childhood in Munich, his law studies, how he joined the party because that this was what we did, how he had climbed the ranks, how he had learned not to ask questions, to do what he was told, to turn a blind eye to what was happening around him. “You think I’m a

monster?”, he said. It was not a question, it was an observation. I have kept silent. He continued. Maybe you’re right, but Monsters are not born victory. They are created by war, by fear, by orders that we cannot refuse. I looked at it, really looked and saw something that I never seen before.

He thought he was victim. He thought that he too suffered, that what he did to me, this what he did to others was something something that was imposed on him, not a choice, an obligation. I felt a rage rising within me, a cold, dangerous rage. I opened the mouth, I almost spoke, almost him say everything I was thinking, but I I remembered Margaot’s words.

Survive first, so I closed the eyes, I lowered my head and let silence speak for me. This that night he didn’t touch me. He is remained seated in his chair, asleep, empty bottle at his feet. Me, I have looked out the window, it was raining. A fine, cold rain at the end of March. I have imagined that this rain had everything, the camp, the war, the hands that had me touched.

But the morning came and nothing had not changed. 3 days later, the contractions started. Not strong at beginning, just a tension in the bottom of the belly. It came and went. I tried to say nothing but Richer noticed. He noticed everything. He called Margot immediately. She examined me in silence then she says “It’s started but it may take hours. Maybe all night.

” Richter became nervous. I had itrarely seen like this. He walked long wide, smoked cigarette on cigarette. He ordered that I transfer to a more equipped room, an old room which once served warehouse, now transformed into something vaguely resembling a delivery room. There was a metal table, white sheets, stained but clean, surgical instruments aligned on a rusty tray.

Margaot stayed with me. She tells me held hands between contractions, told me to breathe, not to push again, to wait. The hours passed, the pain was increasing. It was no longer waves, it was a ocean that was crushing me from the inside. I I was sweating, I was shaking. My body did what it was designed to do, but in the worst possible place.

Richter came in and out. He wanted to be there, but he couldn’t stand to me see suffering. Or maybe he doesn’t couldn’t bear to see that I was suffering because of him, that he had contributed to this situation, that he had kept me here instead of letting me go. Towards midnight, the contractions became unsustainable. Margaot checked.

It’s time, she said. She gave me looked in the eyes. You are strong, victory. You can do it. Think of him only to him. I pushed, I screamed. I felt my body tearing apart. I have thought I was going to die. I even have hoped to die for a moment, just so that the pain stops. But then I heard something. A cry. Small, sharp, furious, my son.

Margaot lifted him up. She wrapped it in a gray blanket. She gave it to me tense. I took him against me and everything disappeared. The camp, the war, Richur, everything. There was only this little face red, his eyes closed, his dots tight. He was alive, he was there and he was mine. It’s a boy Margaot Healthy murmured. I cried.

No relief, no joy, just of total exhaustion. I had survived. He had survived. For the moment was enough. Richter entered. He came closer. He has looked at the baby. His face changed. Something has softened. He held out hand and touched my son’s cheek with one finger. He is beautiful he said gently. What are you going to call it? I have it looked. I thought of Henry.

I thought about the life we had have. I thought about the name we had chosen together sitting in our kitchen months before everything collapsed. Théo, I said, his name is Théo. Richter nodded. Theo, a good name. He stayed there for a while looking. Then he said something that I will never forget. I will do so that nothing happens to him.

You have my word. I didn’t know if I should believe him, but at that time, I didn’t have the choice. The first weeks with Théo were strange. I was a mother in a labor camp. I leave in a locked room. I changed his diapers with salvaged rags. I sang to him in a low voice during that women are screaming in the neighboring barracks.

Margaot came every day check that he was going good. She brought me water porridge, a little powdered milk when she found some. She didn’t smile never, but I saw in his eyes that she was doing what she could. Richter also came, more often than before, but he no longer touched me, not for the first few weeks. He stayed at a distance, he looked at Théo sleep. He asked me questions.

Was he eating well? Is this that he cried a lot? Does I needed something? It was disturbing as if he was trying to play a role, as if he wanted to be someone he wasn’t, a protector, almost a father. But I knew what he was. I knew this that he had done and I knew that this kindness was just another form of control.

One evening he brought something, a small wooden box. Inside he There were baby clothes. clean, soft, probably stolen from a French house somewhere, he gave them to me he said with an almost shy smile. “For Theo,” he said, “I limp, I have whispered thank you because refused would have been dangerous, but inside I hated it.

I hated to see being grateful to the man who had raped me, who continued to keep prisoner, who decided everything in my life. Weather was growing. each day a little stronger, a little more alive and as long as he was safe, I could handle the rest. Then a morning, Margaot entered with a face that I had never seen, white, tense, scared.

She closed the door behind her and whispered. The allies are advancing. They released towns to the north. The Germans prepare to evacuate. My heart jumped. Liberation, the word that I didn’t even dare think more. But Margaot did not smilenot. Victory ! Listen to me carefully. When they evacuate a camp, they will not leave no witnesses.

You understand what that mean? I understood. It wanted to say that we were all going to die or be deported elsewhere. Somewhere worse. You have to leave, Margaot said now, before it’s too late. How ? I’m locked up. There are guards everywhere. She took out a key his pocket. Small, rusty. It opens the back door, the one that overlooks the woods.

There is a hole in the fence 50 m to the east. I did it myself. You take Théo, you run, you don’t stop. And you, I stay, I cover your escape. I will say that you are escaped while I was changing the sheets, which I saw nothing. They will kill. She smiled for the first times since I knew her. A sad but real smile. Victoire, I am old, I no longer have nothing to lose.

But you, you and this little one, you have a whole life ahead you. So take this key and leave tonight midnight. Richter will be meeting with other officers. You will have one hour, maybe two. She put the key in my hand, then she left. I have looked at this key all day. I squeezed it so hard that it left a mark in my palm.

I knew that It was my only chance, but I had fear. Fear of the dark, fear of wood, afraid of what awaited me outside and above all afraid of what would happen to Theo if I got caught. But to stay was to die anyway. So, I decided. At midnight I wrapped Theo in all the blankets I had. I tied it against my chest with a shawl.

He was sleeping. Thank God. I went towards the back door. I inserted the key. My heart was beating so hard that I was afraid people would hear it. The lock clicked. The door opened. The air cold hit me in the face. It smelled the wet earth, the bread, the freedom. I looked behind me at last time, then I ran.

I don’t didn’t know where I was going. I was just following is as Margaot said. My feet were sinking into the mud. The branches scratched my face. Theo started to cry. I dumped my hand on his mouth gently, just to muffle the sound. Fall, my angel, fall, mom is here. I found the hole in the fence, small, barely enough big.

I slipped aside, protecting Theo with my arms. The barbed wire tore my dress, my skin, but I passed. Then I ran, I ran like I never had before ran, through the woods, through the night. I didn’t know where I was going. I just knew I had to get away, put as much distance as possible between me and this hell. After a hour, maybe two, I fell.

Exhaustion overwhelmed me. My legs don’t carried me more. I collapsed against a tree and trembling. Theo was now crying loudly. He was hungry, he was cold. I too tried to lighten it. My hands were shaking so much that I could barely hold. But he took the breast, he drank. And during that moment, there in the dark, in the middle of nowhere, I felt something that I had no longer felt for months. hope.

We were going to survive. We had to survive. But then I heard voices far away then closer, lamps torches sweeping the trees, dogs barking. They were looking for me. I squeezed Theo against me and I sank deeper into the woods. I had no more strength. My legs were shaking, my lungs were burning. But I continued because to stop it was to condemn us both.

The voices were getting closer, the dogs too. I could hear their growling, their paws hammering the ground. Richter was with them. I I recognized his voice. He shouted my name. Victory, come back. You will not survive not outside. Think about the baby. Think about baby, that was exactly what I was doing.

And that was why I will never come back. I found one small, icy river, but it flowed quickly. I remembered something my father told me when I was a child. Dogs lose the trace in the water. I entered. The water came up to my knees. Cold, so cold that my eyes seemed to freeze. Theo screamed. I put it back together higher against me, trying to keep dry. Then I walked.

I have walked in this river for what seemed like hours. The barking decreased and then stopped arrested. They had lost my track. I came out of the water to a place where the trees were my densest. I have found a hollow trunk. I slipped inside with Theo. We were soaked, frozen but hidden. I waited all night.

I listened to the sounds of the forest. Every branch cracks made me jump. Every cry bird sounded like a signal. Butno one came. At sunrise, I came out. My clothes were still damp. Theo was pale, his blue lips. I had to find help. Quickly, I walked all the way morning. I didn’t know where I was. Everything looked the same. trees, hills, muddy paths.

Then I saw smoke, a chimney, a farm. I hesitated. And if it was collaborators? What if they delivered me to the Germans? Met needed warmth, food. I didn’t have the choice. I approached slowly. It was a small farm in stone, a henhouse, a vegetable garden. A old woman was outside, feeding the chickens.

She saw me, she frozen. I moved forward, my hands lifted. Please, I said, my voice was harsh, broken. If he Please help us. She looked at Theo, then me. She saw my torn dress, my bare and bloody feet, my emaciated face. And she understood. Entered, she said simply. Her name was Madeleine Girou, years old, widow.

Her husband died in 1940 at the start of the war. His son had joined the resistance and she didn’t know not if he was still alive. She lived alone for 3 years and she hated the Germans more than anything anyone I’ve ever met. She gave me installed near the fire, gave me dry clothes, a bowl of hot soup. She examined Theo.

He’s fine, she has said, just cold and hungry like you. I cried for the first time since weeks. I really cried. Madeleine didn’t ask me any questions. She just put her hand on my shoulder and said: “You are safe now.” I slept soundly. For the first time in months, when I woke up it was night. Theo was sleeping next to me, wrapped in a clean blanket.

Madeleine was sitting by the fire knitting. “They came,” she said without looking up. “The Germans afternoon, they were looking for a young woman with a baby. I told them that I hadn’t seen anything. They searched the barn. But not the house, they are gone. My senses froze. They are going maybe come back but not this evening and tomorrow you will be gone where there is a network, resistance.

They pass people to the liberated areas. I will put you in contact with them but you might have to walk again several days. I nodded. I can do it. She finally looked at me. What is this What did they do to you, my little one? I don’t have not answered. I couldn’t. The words did not exist. She understood. She returned to her knitting.

One day, this war will end and you will have to continue live. It won’t be easy, but you will do for him. She showed Theo chin. She was right. I will for him. Two days later, Madeleine led me to a point of appointment. A man was waiting for him. John. Thirty years old, thin, nervous. resistant. He guided me through paths secrets, forests, tunnels.

We We only traveled at night. We we hid the day. There were other fugitives with us, Jews, political prisoners, deserters. We were a strange group, silent, all bound by the same fear and the same hope. One night we heard shooting. German soldiers patrolled the area. Jean made us sleep in a ditch. We stood still for hours, mouth until neck holding our breaths.

Theo has started to cry. I covered her mouth with my terrified hand. The steps came closer and then moved away. We we survived. Again. After 9 days of walking, we reached a area liberated by the Americans. Of soldiers in khaki uniforms, flags French, people who were crying joy in the streets. The war was not not finished.

But here, for the moment, she was far away. Jean took me to a reception center for refugees. Of women of the Red Cross told me registered, gave me papers temporary workers, asked me questions on my family, on wanted to go. You said, I want to go back to Tul. But when I came back, three weeks later late, there was nothing left of my life from before. Maon had been bombed.

Family games

My parents had been deported. Henry Henry had been hanged by the Germans the day after my kidnapping in retaliation. For having resisted, I learned all this from a neighbor who had survived. He told me with sad eyes as if he were apologizing for telling me that my life had died at the same time as the people I loved.

I held Theo against me and I looked at the ruins of my house. There was nothing left, no photos, no memories, no cradles in chains, just stones and ashes. I stayed there for a long time, then I turned my back and I started walking. The years after the war were blurred. Iremember certain things clearly brutal.

Theo’s weight in my arms, his first steps, his first words. But the rest is like someone had erased pieces of my memory. Maybe that’s what the trauma. He keeps what matters and throws away the rest. I settled in Lyon, a city big enough to disappear, anonymous enough to start again. I have found work in a factory textile.

I sewed buttons on coats. 10 hours per day, 6 days per week. I earned enough to rent a tiny room, a bed, a table, stove. It was enough. Theo was growing up. He was a child calm, too calm sometimes, as if he felt he should be quiet so that we stay safe. I sang him the same lullabies as my mother sang to me. I told him about stories about his father, Henry the carpenter, Henry the brave, Henry who loved us more than anything.

I don’t have him never told the truth about his birth. Never said where he was born, never said what that I had experienced while I wore. How could I? How to explain to a child whose first breath had been caught in hell? The others women from the factory asked me questions questions. Where is your husband? Why do you don’t wear a wedding ring? The father of Theo, he died in the war.

I I answered yes. It was simpler, fewer questions, less stares. But at night I had nightmares. I woke up in a sweat, my heart beating, sure to hear boots in the hallway. Certain that Richter was there, that he was coming to take me back. I got up, checked the door, watched Théo sleep and I repeated to myself : “It’s over, you are free, he can’t touch you anymore.

” But even free, I was still a prisoner, a prisoner from my own memory. Enc, I met a man, Marcel. worker in the same factory, kind, patient. He invited me for coffee. I have refused. He insisted gently, without pressure. Finally, I accepted. We We talked about everything and nothing. He told me recounted his life.

He had lost his wife during the war. A bomb. He raised his daughter alone. He understood what it was about rebuilding on ruins. We became friends. Then more. He proposed to me in 1954, I said yes, not for love, not for beginning, but because it offered something something I no longer had, security. He adopted Théo, gave him his name, became the father my son never had never had.

And little by little, something something in me has softened, not healed, never healed, but softened. Marcel never asked me any questions on the war. He knew I had scars. He saw them, the physical and the others. But he didn’t force anything. He was waiting. And sometimes, late at night, I told him pieces. Never everything, never the details, but enough so that they understand why I woke up screaming.

Why don’t I I couldn’t stand someone touching me days, why was I checking obsessively the locks of doors. He listened, he did not judge, he held my hand. and that was enough. Théo grew up a good man, intelligent, kind, hardworking. He is became a professor, he got married, he gave me three grandchildren and each every time I looked at them, I thought “You won, victory, you survived and you created something beautiful despite everything.

” But I still wore the secret like an invisible weight. Theo does not didn’t know. Marcel didn’t know really, no one knew. During decades I thought I I’ll take it to my grave, that it was better this way, that certain things should not be said. Then in 2004, I saw a documentary on television on French work camps during the war, on women who had been kidnapped, raped, forced to carry the children of their executioners and for the first time I heard other voices, other women who recounted what I had experienced.

They were old like me. their face marked by time and pain, but she spoke, she testified and I understood that I had to do it too. I contacted the directors of documentary. I told them that I had a story, that it deserved to be heard. They came to my house, installed a camera, a microphone and asked to speak. I was one year old.

Marcel had died three years earlier. Theo was an adult with his own life. I had nothing left to protect, nothing left to lose. So I spoke, I have everything told. The camp, wealth, rapes, the birth, the escape, everything. It has took hours. I cried sometimes. I I stopped, I started again. The directors didn’t interrupt me, they just recorded.

When I finished, one of them asked me why now? Why after so much years? I thought long beforeto respond. Then I said because for 60 years I was ashamed ashamed of what had happened to me. As if it were my fault, as if I should have done something different. But now I know it wasn’t my shame, it was time and I refuses to die wearing it.

The documentary was released in 2005. Ma game lasted 15 minutes. 15 minutes on 60 years of silence. The reactions were intense. Some people have wrote to thank me, to tell me that my testimony had helped them to understand something in their own life. Others have accused me of lie, seek attention, sully the memory of the war.

Theo has watched the documentary. He called me after. He was crying. Mom, he said “Why didn’t you ever tell me anything?” because I didn’t want you to feel marked by that. I wanted you live without carrying this weight. But this is not a burden, mom, it’s your strength. You survived. You protected me. You have built a life. Despite everything.

These words broke me and healed me at the same time time. I lived 8 years after this documentary. years during which I received letters, calls, invitations to testify in schools. I did it when I could because I thought that young people should know, became understand that war is not just about not to battles and treaties, that she also plays out in women’s bodies, in the wombs of mothers, in the silences that last for decades.

In 2013, I fell ill. Cancer. The doctors told me that I had no only a few months. I refused the treatments. I was 90x years old. I had lived long enough. Theo came to me see every day. He read to me books, told me about his little ones children, held my hand. A afternoon, he asked me “Mom, did you any regrets?” I thought for a long time.

Then I said “Just one. I regret not having spoken sooner, not having told other women who have experienced the same thing, that they were not alone, that she had not brought the shame, that survival itself was an act of resistance. I died on November 7, 2013 at home, surrounded by my family. Theo held my hand.

Family games

His daughter read poems. I closed my eyes and for the first time since 1944, I I was no longer afraid. Today, if you listened to this story until But, you are a witness. You wear now a part of my memory. And maybe that’s all I can ask. Let someone remember, let someone know what happened. Not to complain, not to ask pity, but to tell the truth.

Because that the truth, as painful whatever it is, always deserves to be said. My name was victory of the cross. I have survived the war. I survived my executioners. And even now, years after my death, my voice exists again. This is my final victory. This voice you just heard doesn’t exist more.

Victory of the Cross died in 2013, taking the scars with it of a war that never ended truly finished in his body. But his testimony remains alive. Each spoken word was an act of courage. Every detail shared was a victory against the silence which still suffocates thousands of women around the world. If this story touched you, if it awakened something in you, don’t don’t let it stop here.

Subscribe to this channel because these stories do not must never be forgotten. Because collective memory is built through those who agree to carry the weight of truth. By subscribing, you become a guardian of these voices. You tell the survivors that their pains were not invisible, that their survival mattered, that 60 years of silence have not been vain.

Leave a comment, say where from you listen to this story. That you be in Paris, Montreal, Dakar or Tokyo, your presence matters. Each comment is proof that Victoire did not speak into the void, that his son Théo did not grow up in shame. that the ten women taken away that night of March 1944 did not die without witness.

Just write your city or a word or a thought. anything who says “I listened, I remember” and if you know someone who wears a similar secret, someone who has no never dared to speak, share this history with her because sometimes hear the voice of another survivor is what frees ours. The war is not only in books of history.

She lives in the bodies of women who survived, in the silences of families, in the questions never asked. Victory has broke his silence at 81 years old. How many women are still waiting thinking that he is too late? It’s never too much late for the truth. Mr.